Raila Amolo Odinga, a veteran Kenyan political leader and one-time prime minister, has long cast himself as an anti-establishment firebrand, despite belonging to one of the country’s top political dynasties. But his decision to strike an alliance with his arch-rival, President Uhuru Kenyatta, and secure the ruling party’s backing risks taking the shine off his brand as he vies yet again for the top job in Tuesday’s elections.

The Kenyatta and Odinga families have dominated Kenyan politics since the country won independence from Britain in 1963. Uhuru Kenyatta’s father Jomo was the East African nation’s first president while his rival Jaramogi Oginga Odinga — Raila’s father — served as vice president.

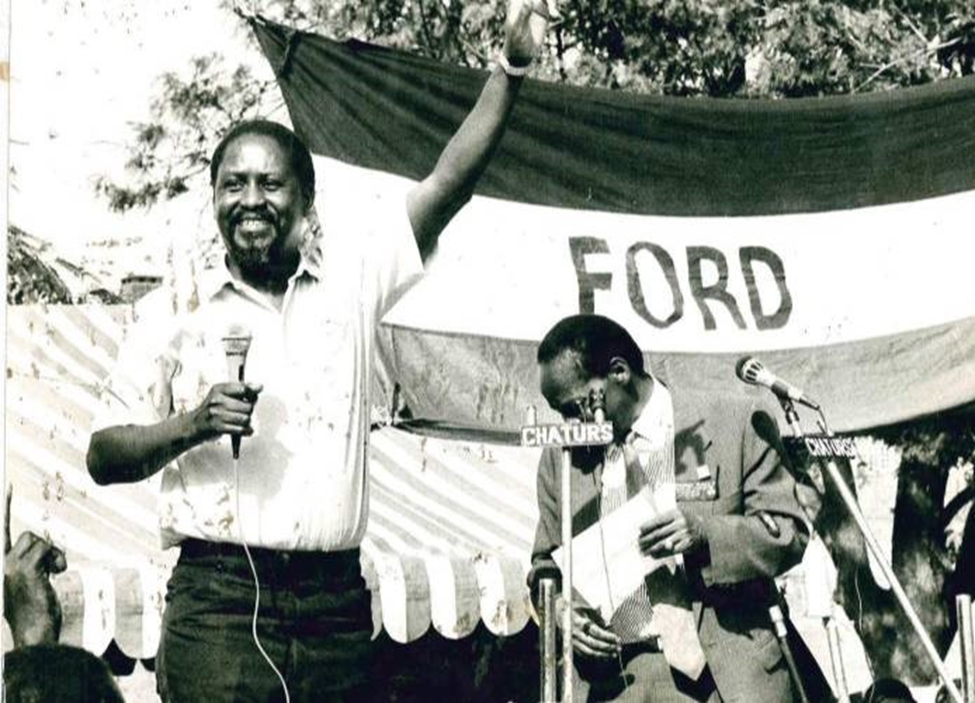

Now 77, Raila Odinga’s early years in politics saw him spend much of his time in prison or in exile as he fought for democracy during the autocratic rule of president Daniel arap Moi. A member of the Luo tribe, he entered parliament in 1992 and ran unsuccessfully for the presidency in 1997, 2007, 2013 and 2017, claiming to have been cheated of victory in the last three elections.

The 2007 polls in particular — which many independent observers also considered deeply flawed — cast a long shadow over Kenyan politics, unleashing a wave of ethnic violence that pitted tribal groups against each other and cost more than 1,100 lives.

Few therefore expected Odinga and Kenyatta to shake hands and draw a line under decades of vitriol in March 2018. Known universally as “the handshake”, the pact stunned Odinga’s colleagues and supporters, effectively leaving Kenya without an opposition.

‘Nobody’s stooge’

The East African powerhouse is due to hold high-stakes presidential and parliamentary elections on August 9, but Kenyatta — who cannot run for a third term — will not be on the ballot.

Simon MAINA / AFP

When Kenyatta — a two-time president who cannot run for a third term — endorsed Odinga for the presidency earlier this year, observers speculated that Kenya’s best-known agitator had traded his autonomy for a chance to be in power. Odinga has hit out at the claims, telling a press conference earlier this month that Kenyans “know that I am an independent person, that I am a person of conscience, and with very strong convictions”.

“I cannot be somebody else’s stooge or candidate.”

Odinga’s elevation came at the expense of Kenya’s Deputy President William Ruto, who found himself frozen out as the erstwhile foes drew closer.

It also came loaded with risks for the veteran leader, with Ruto now positioning himself as a politician looking to upend the status quo and stand up for the “hustlers” trying to make ends meet in a country ruled by “dynasties”.

“Raila is quite conscious that a lot of the support he enjoys is because he has been an anti-establishment figure for so long,” said Gabrielle Lynch, professor of comparative politics at the University of Warwick.

“The handshake has undermined that narrative,” she told AFP.

Odinga, who was born on January 7, 1945 and is fondly known as “Baba” or “daddy” in Swahili, is now caught in a complex balancing act.

“He has a lot of trust to build, especially in his main voting bloc,” Kenyan political analyst Nerima Wako-Ojiwa told AFP.

Polarising politician

While his supporters consider Odinga a much-needed social reformer, detractors see him as a rabble-rousing populist, unafraid to play the tribal card. A charismatic speaker, he has a reputation for being stubborn and sometimes short-tempered.

In the eyes of some observers, his crowd-pleasing skills have diminished in recent years, attributed to advancing age and ill health. With his speech notes in hand, he often stumbles and labours over his words — especially in English. Speaking off-the-cuff in his native Swahili, however, he retains the ability to inspire.

Passionate about reggae, he has adopted South African star Lucky Dube’s song “Nobody Can Stop Reggae” as an unofficial motto for his campaign in recent years. An Arsenal fan, he credits his love of football for helping him develop a philosophical attitude towards the rough-and-tumble world of politics.

“You lose some, you win some. It is painful but that is the way to perfection,” he said in an interview with AFP last year.

Raised an Anglican, he later converted to evangelicalism and was baptised in a Nairobi swimming pool by a self-proclaimed prophet in 2009. The Bible even crept into Odinga’s 2017 campaign with his repeated promise to lead his followers to Canaan, the mythical “promised land”.

He studied engineering in communist former East Germany and named his eldest son Fidel, who died in 2015, after the Cuban revolutionary. Although not as wealthy as Kenyatta or Ruto, Odinga sits at the head of a business empire with stakes in energy companies.

Married to his wife Ida for almost half a century, Odinga has three surviving children and five grandchildren.