With runaway inflation eating into incomes, staple foods have vanished from the tables of Zimbabweans like Emina Chishangwe, who lives in a poor dormitory town south of the capital Harare.

“I can’t remember the last time I ate meat. It has become a luxury for some of us,” said the 57-year-old single mother of two adult sons.

Zimbabwe has the highest inflation rate in the world, according to Steve Hanke, a professor of Applied Economics at Johns Hopkins University, who believes it can only be remedied by the full adoption of the US dollar.

The situation has quickly worsened this year as the Russian invasion of Ukraine compounded with black market foreign exchange has depleted the value of the Zimbabwe dollar.

“The parallel market is to blame to a large degree for the spiralling inflation,” AgriBank chief economist Joseph Mverecha told AFP.

Zimbabwe’s economy has been on a downturn for nearly two decades, marked by shortages of cash and food.

Distrust has led people to exchange their cash for US dollars, further driving down the local currency.

Inflation soared to 191.6 percent in June, up from 60 percent at the beginning of the year, driving prices of goods ever upwards.

The rate dwarfs even the 41 percent inflation in war-torn Ukraine.

A kilo of choice beef now costs ZWL8,768 ($21.92) and five kilos of chicken drumsticks ZWL21,000 (US$65.22) — the equivalent to a civil servant’s average monthly salary.

Chishangwe, who runs a vegetable stall in Chitungwiza town, and her sons have two meals a day instead of three, usually a thick cornmeal porridge called sadza and kale or tiny dried sardines.

‘Anguish’

Rising fuel prices forced Edwin Matsvai to downgrade from a fuel-guzzling Toyota Land Cruiser to a more economic Honda Fit.

“My friends made jokes about me ‘stepping down’ when I made the change but now some of them are considering following suit,” said Matsvai, a car salesman.

Petrol rose to US$1.77 per litre this month from US$1.41 in January.

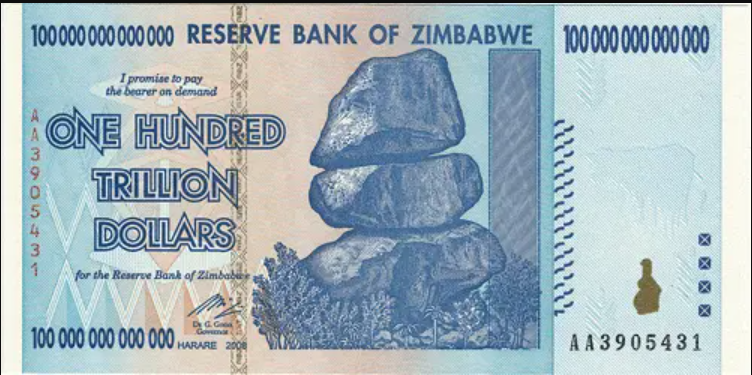

Zimbabweans endured and survived some of the worst hardships of 2008 when hyperinflation saw the central bank mint a one-trillion-dollar note.

Growing discrepancies between incomes and cost of living, forcing people to make tough decisions of how and where they live, is taking a toll on mental health, according to specialist psychiatrist Isabel Chinoperekwei.

“I see many of them coming with depression, anxiety disorder and also alcohol abuse,” said Chinoperekwei, who has a private practice in Harare.

It’s not just working professionals feeling the anguish.

“I have seen adolescents who have changed schools because their parents could no longer afford the schools they were going to,” Chinoperekwei said. “They find it hard to cope.”

Many blame the country’s leaders.

“The old men have failed us,” said Matsvai, referring to the government. “If they don’t act swiftly and fix the economy, it will cost them in next year’s general elections.”

Already in the March by-elections, the long-ruling Zanu-PF party lost to the opposition Citizens’ Coalition for Change (CCC) which was formed barely three months earlier.

The southern African nation is due to hold general elections in 2023.

‘Hand to mouth’

Analysts say the current political and economic landscape now mirrors the crisis leading into the 2008 election, which saw ex-ruler Robert Mugabe nearly fall from power.

“People who are earning starvation wages, those without jobs and all those who are feeling the pinch of the rising cost of living have lost faith in Zanu-PF,” said Takavafira Zhou, a political scientist at Masvingo State University.

“The only hope lies in a new government that will give (the public) reprieve.”

Zanu-PF has been in power since 1980, when British colonial rule ended. Current president Emmerson Mnangagwa took over from Mugabe in a 2017 military coup, pledging to fix the moribund economy he inherited.

The risk of losing power in upcoming polls is now pushing Zanu-PF to “frantic measures” to halt price hikes that have plunged millions into deeper poverty, said economist Prosper Chitambara.

“The world over, no ruling party is expected to do well in an environment of chronic high inflation,” said Chitambara, of the think-tank Labour and Economic Development Research Institute of Zimbabwe.

Last month Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube announced a raft of monetary policies including maintaining the dual use of the US dollar, adopted after the 2008 hyperinflation, and the Zimbabwe dollar reintroduced in 2019.

Minimum interest rates more than doubled to 200 percent last week.

The country is also introducing gold coins “as a store of value” starting July 25.

But those are for the rich.

“The ordinary citizens, those who are struggling and living from hand to mouth are not going to afford it,” said Chitambara.