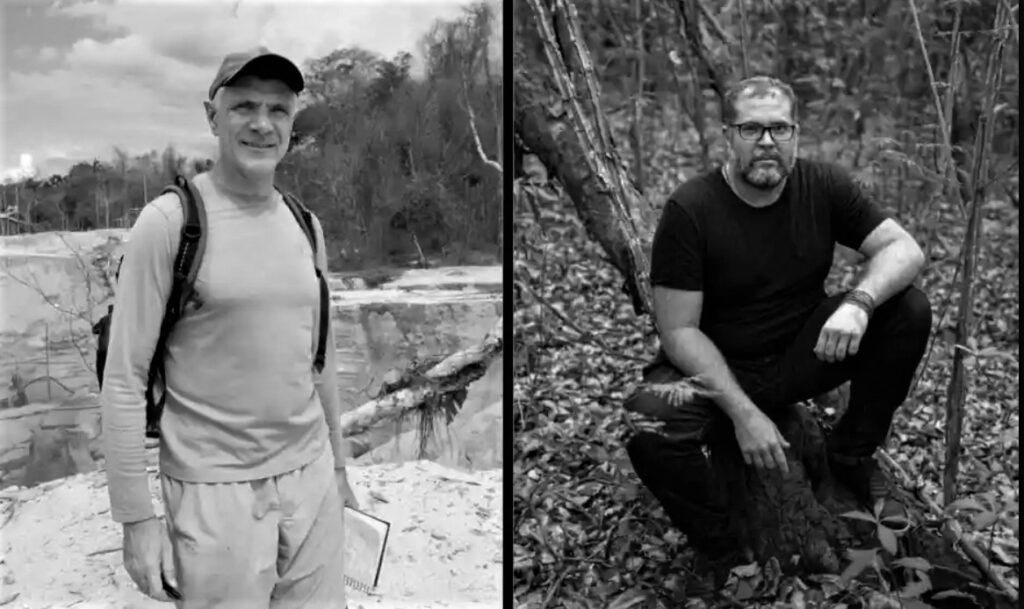

Veteran British freelance journalist Dom Phillips and respected Brazilian indigenous expert Bruno Pereira share a passion for the farthest reaches of the Amazon rainforest, where they disappeared three days ago.

The pair were last seen early Sunday traveling by boat in Brazil’s Javari Valley, a far-flung jungle region near the border with Peru, where Phillips has been researching a book.

The region has seen a surge of criminal activity in recent years, including illegal logging, gold mining, poaching and drug trafficking — incursions Phillips has reported on and Pereira has vigorously fought.

They had already traveled there together in 2018 for a feature story Phillips wrote in British newspaper The Guardian on an uncontacted tribe — one of an estimated 19 in the region.

“Wearing just shorts and flip-flops as he squats in the mud by a fire, Bruno Pereira, an official at Brazil’s government indigenous agency, cracks open the boiled skull of a monkey with a spoon and eats its brains for breakfast as he discusses policy,” it began.

That memorable introduction neatly sums up both men, courageous adventurers who love the rainforest and its peoples, each defending the Amazon in his own way.

Dom Philips

Phillips, 57, started out as a music journalist in Britain, editing the magazine Mixmag and writing a book on the rise of DJ culture.

Lured by DJ friends, he set off for Brazil 15 years ago, falling in love with the country and his now wife, Alessandra Sampaio — a native of the northeastern city of Salvador, where the couple lives.

Reinventing himself as a foreign correspondent, Phillips has covered Brazil for media including The New York Times, Washington Post, Financial Times and Guardian, where he is a regular contributor.

“Dom is known as one of the sharpest and most caring foreign journalists in South America,” a group of friends and colleagues said in a statement, urging the Brazilian authorities to redouble their search efforts.

“But there was a lot more to him than pages and paragraphs. His friends knew him as a smiling guy who would get up before dawn to do stand-up paddle. We knew him as a caring volunteer worker who gave English classes in a Rio favela.”

Phillips has traveled in and written about the Amazon for dozens of stories, winning a fellowship from the Alicia Patterson Foundation last year to fund his project to write a book on sustainable development in the rainforest.

The project took him back to the region he loved.

“Lovely Amazon,” he posted on Instagram last week, along with a video of a small boat winding down a meandering river.

Bruno Pereira

Until recently working as a top expert at Brazil’s indigenous affairs agency, FUNAI, Pereira was head of programs for isolated and recently contacted indigenous groups.

As part of that job, the 41-year-old organized one of the largest ever expeditions to monitor isolated groups and try to avoid conflicts between them and others in the region.

Fiona Watson, research director at indigenous-rights group Survival International, called him a “courageous and dedicated” defender of indigenous peoples.

“He’s an immensely passionate person, and extremely knowledgeable,” she said.

Pereira was especially revered for his knowledge of the Javari Valley, where he was also FUNAI’s regional coordinator for years.

But he is currently on leave from the agency, after butting heads with the new leadership brought in by far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, who faces accusations of dismantling indigenous and environmental protection programs since taking office in 2019.

Pereira “was effectively forced out at FUNAI, basically because he was doing what FUNAI should be doing and have stopped doing since Bolsonaro took office: standing up for indigenous rights,” Watson told AFP.

Pereira has frequently received threats for his work fighting illegal invasions of the Javari reservation.

That includes helping set up indigenous patrols. He and Phillips were on their way to a meeting on one such patrol project when they disappeared.

“Every time he enters the rainforest, he brings his passion and drive to help others,” Pereira’s family said in a statement.

He and his partner have three children.