The law is a landmark reform implemented by the South American country’s new leadership after the United States captured socialist strongman Nicolas Maduro in a deadly raid on Caracas last month.

But the amnesty, unanimously approved by Venezuela’s National Assembly on Thursday, does not extend to those who have been prosecuted or convicted of promoting military action against the country.

That could exclude opposition leaders like Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Corina Machado, who has been accused by the ruling party of calling for international intervention like the one that ousted Maduro.

Detractors also fear the law could be used by the government to pardon its own and selectively deny freedom to real prisoners of conscience.

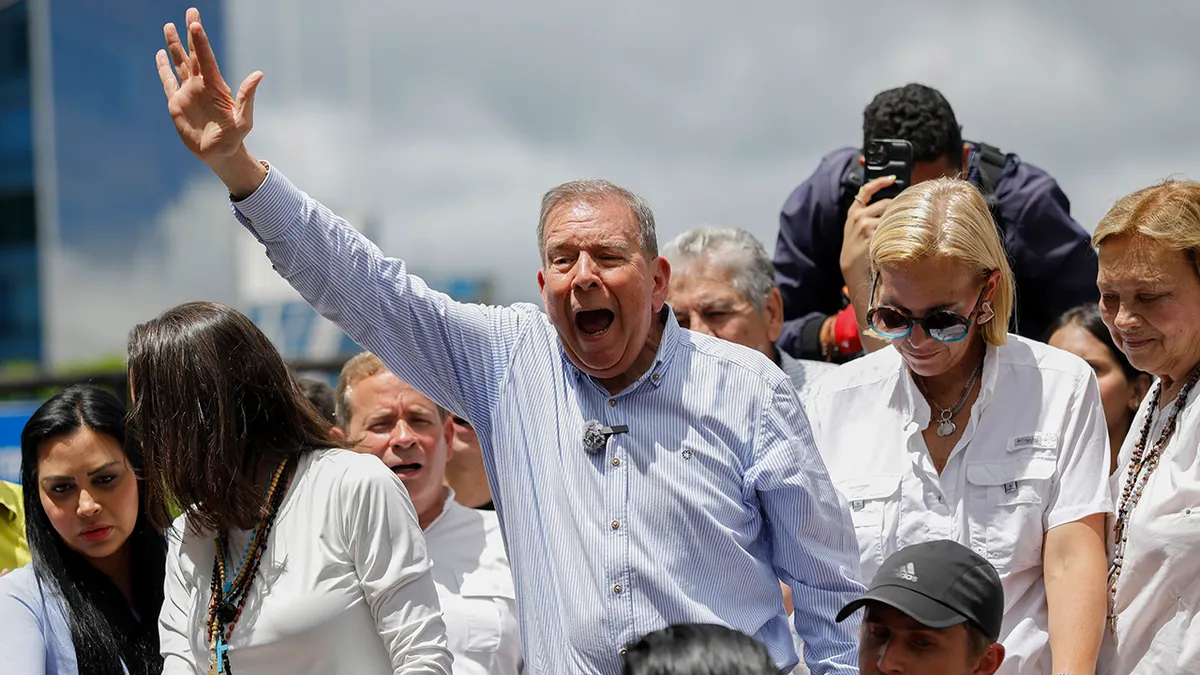

“I am convinced that we will be able to craft an amnesty suitable for an entire country,” Gonzalez Urrutia, widely considered the rightful victor of 2024 presidential elections marred by fraud allegations in which Maduro was declared the winner, wrote on X.

A “legitimate” amnesty must come with “truth, recognition and reparation”, added Gonzalez Urrutia, who fled to Spain in 2024 as the authorities cracked down on post-election protests.

“A responsible amnesty is the transition from fear to the rule of law. It is the pledge that power will not be exercised again without limits and that the law will be above force,” he said.

“We have the responsibility to document our historical memory before the facts disappear,” Gonzalez Urrutia warned.

Venezuela’s interim president Delcy Rodriguez — previously Maduro’s vice president — pushed for the amnesty law under pressure from Washington, which has cooperated with her government in return for access to Venezuela’s enormous oil reserves.

imm/ds/rmb